Petersburg officials are reviewing the community’s response to a tsunami warning from the January 4th earthquake that rattled Southeast Alaska and sent residents scrambling to higher ground in the middle of the night. The voluntary evacuation went smoothly by many accounts but also highlighted some possible areas of improvement.

For iFriendly audio, click here:

Petersburg’s public safety advisory board discussed the tsunami warning response at a meeting earlier this month. Police chief Jim Agner thought the community’s response went well under tough circumstances. “Because this was some of the worst possible conditions,” Agner said. “It was just above freezing, it was the middle of the night, it was raining, it was about a miserable thing and the entire community did very well.”

A tsunami warning was issued following a magnitude 7.5 earthquake that rocked the region just before midnight on January 4th. It was located off the coast of Southeast about 71 miles from Craig. Here in Petersburg, residents were urged to move inland to higher ground. Many received notice of the warning through the community’s Code Red notification system. Police also announced the evacuation over loudspeakers while driving along the waterfront.

Agner told the board that dispatchers moved out of the downtown police building and worked from a communications trailer and from the new fire hall. “We have done a couple of sort of dry runs but there are some things you just don’t do,” he said adding, “And one of them was throwing the switch and we turned off this police facility. And when I left, I walked out to close the door and for probably the first time in 50 years, no one was in that building for a fairly significant amount of time. We walked away and we seamlessly made the conversion on both phones and radios.”

Agner said other things did not go as hoped, the Code Red warning system for instance. He said the emergency warning phone system notified many people about the tsunami danger, but far fewer people received the “all-clear” warning.

The board agreed that community members should prepare emergency bag with supplies in case people cannot return to their homes immediately.

Board member Jim Engel said another need to consider in planning was a place to gather for people without vehicles. He said police dropped off one couple where he was waiting at the Hammer and Wikan parking lot. “You know obviously when the hospital was evacuated they were brought to Mountain View manor,” Engel said. “But coming up with a pre-designated place for that population of people who don’t have a vehicle to sit in, that don’t have the ability to just say hey can I jump in your car. What do you do with that group? It isn’t necessarily a large population but it’s enough that the hour and a half they were up there they would’ve froze.”

Other people waited out the warning at the Petersburg Indian Association, Alaska Airlines terminal and the baler facility to name a few. And some residents chose not to leave their homes. Many evacuated to the location originally designated as the community’s gathering spot in Petersburg disaster response plan, the ballfields. At a meeting of the borough assembly this month, borough manager Steve Giesbrecht acknowledged problems with sending so many people to there. “Everybody goes to the ballfield and then we had a mess at the ball field,” Giesbrecht said. “You know the lighting is not as good, there’s only one way in and out, bathrooms weren’t open. So it may not be long-term the best place to send the whole town to all at once, so we gotta work through that a little bit.” Petersburg’s local emergency planning committee will revisit the community’s plan and determine other evacuation sites.

Giesbrecht also told the assembly the borough was looking into the cost of completing an inundation study. “It’s seemingly spending money on something we maybe already know but it basically says in the event of a tsunami it starts to outline where we should send people,” he said. “And today, because we’ve never done that we have to tell people the standard response which is one mile inland or 100 feet up. Which kind of limits where we can send people.”

An inundation study is one requirement for designation as a tsunami ready community. That’s a National Weather Service’s program aimed at helping coastal areas plan for potential impacts of an ocean wave. Other requirements are developing a formal tsunami plan, holding emergency exercises and posting signs for evacuation routes and safe zones. 16 Alaska communities, including Juneau Sitka and Yakutat in Southeast, are designated tsunami-ready.

There are a few tsunami zone signs are already posted on Mitkof Island. Drivers might have noticed the signs on Mitkof Highway near the Crystal Lake hatchery south of Petersburg. Those mark safe zones for the event of a failure of the Crystal Lake dam which could drop reservoir water down the mountain onto the roadway and buildings below.

Sandy Dixson, fire and ems director and chair of the Local Emergency Planning Committee said an inundation study and tsunami ready designation for the community may depend on the cost and finding funding. However, short of a full study she says the community could map out safe areas. “It probably wouldn’t hurt to start with the 100 foot elevation because that’s just a general rule of thumb that the state has put out there, the 100 foot elevation mark or one mile inland and it would be good for people out the road especially for them to find out where that is for them, where they should go,” she said. “And obviously that would be the cheaper route.”

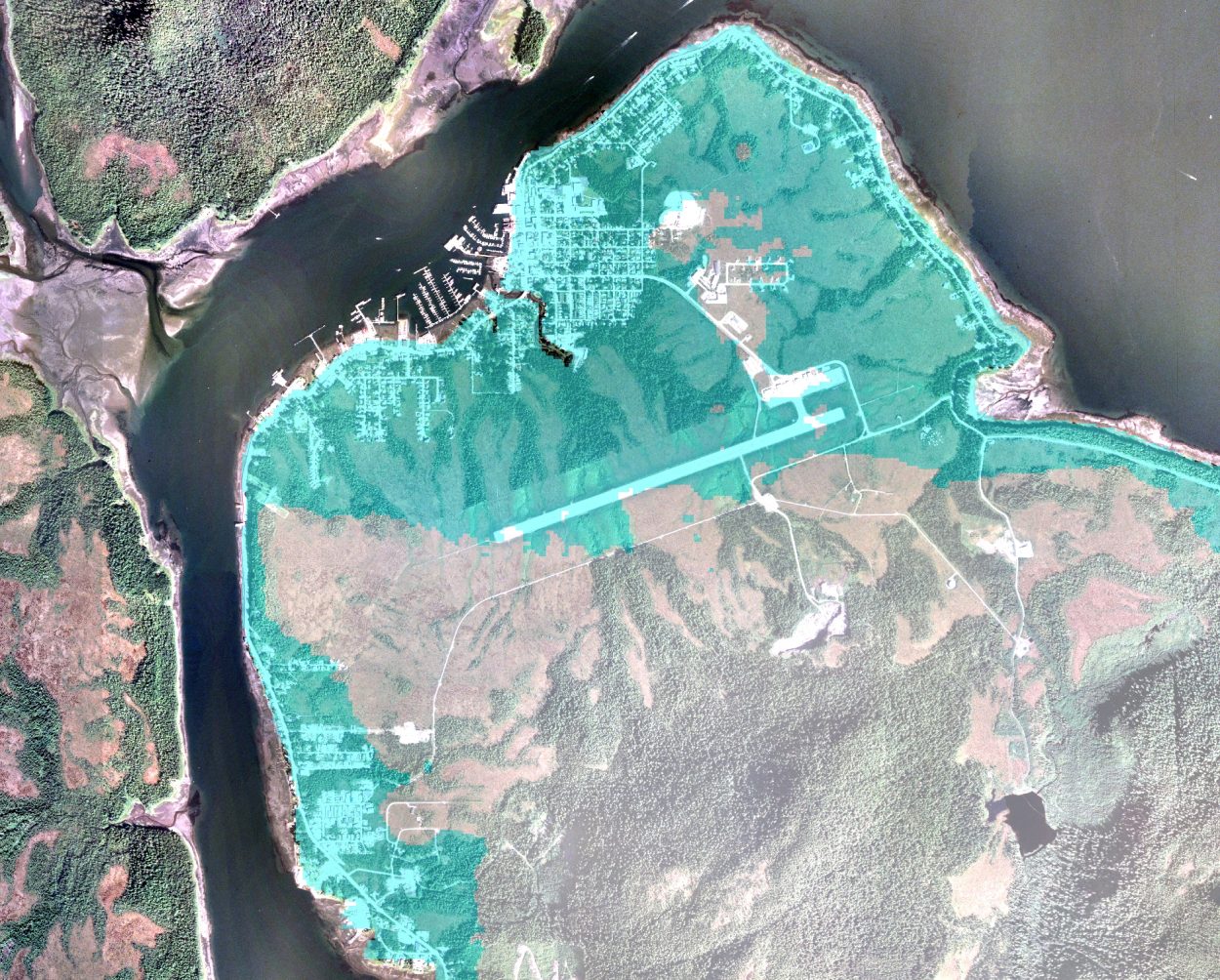

The area in blue shows elevation below 100 feet on the north end of Mitkof Island. Areas not colored blue are above 100 feet. (Image courtesy of Emil Tucker)

Dixson agreed the response January 4th went well but says communication is always an issue. The warning siren failed and officials are looking into that problem. Also a number of people did not receive notification on the Code Red system, including Dixson, one of system’s administrators. Dixson said she’s heard from others who were not notified. “And my recommendation to them was to go into the system to make sure that you are registered and that you did put appropriate phone numbers in and then again trying to trouble shoot where that disconnect was because I should’ve, I have four numbers listed and again I didn’t get the calls,” Dixson said. “There is some type of disconnect there and we’re trying to figure that out.”

Other than a test of the system, the evacuation was the first community-wide call out on the Code Red system. Dixson encouraged people to plan ahead and take personal responsibility for readiness. “Don’t think of just a tsunami but what if their house was damaged what would they have done? What if they had been where the power’s been out. So it’s not just big events where it affects the whole community, what about just their neighborhood or just their home. So being ready, you know what medications do you need to go, do you need money, do you need a change of clothes, if you have babies do you need diapers and wipes, kind of thing. We as the city cannot provide that for each individual family. So we can do general things.”

She also cautioned people about getting information from reliable source, like the radio or code red system and being careful about unsubstantiated information sent around on social media.

The Alaska Earthquake Information Center says January’s quake was the largest recorded in Southeast since a 6.8 temblor in June of 2004. Other strong earthquakes also were recorded on the same fault in August of 1949 and July of 1972.