Delores Churchill shows a photo album of her weaving during a recent visit to Petersburg. Photo/Angela Denning

Audio Player

Dressed in black with her silver hair neatly parted to one side Delores Churchill sits on a couch surrounded by photos of her work. Some are in albums and others are spread out on the seat and she can remember details of each one.

Delores Churchill was born on Canada’s Queen Charlotte Islands. She started weaving at age five at school as a way for Haida speaking children to learn English. The weaver was Churchill’s mother, Selina Peratrovich.

“And because she was my mother I wouldn’t listen,” Churchill said. ” I just kept making my own style basket.”

She doesn’t remember the details but the basket wasn’t cylindrical like her mother wanted. The school’s baskets were sent to a contest in Victoria, British Columbia where Churchill’s won first place. The prize was a whopping $5.

“In 1930 $5 was like a hundred now,” Churchill said. “So, my mother called me to the front. She gave me the blue ribbon. And then she called my best friend up and she gave her the $5. I was so angry the blue ribbon she had pinned on me I threw on the ground and I stomped on it and said, ‘I hate basketry anyway’ (laughs).”

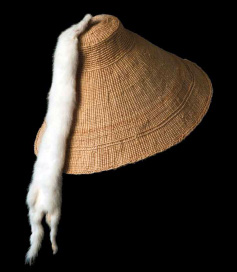

Churchill didn’t try weaving again until she was an adult. She realized that the only Haida weavers left were her mother and sister so she decided to take a class at the community college in Ketchikan where her mother was the teacher. At first her mother didn’t want her in the class but the head of the art department convinced her otherwise. Learning the craft was a good thing too because now Churchill is known all over the world as an expert Haida weaver of baskets, robes, hats, and other regalia. She uses spruce root and red cedar bark.

“With the cedar bark all you do is pull the bark off the tree, you split it in several layers and then you could pull it through a stripper so that you have even warp and even weft,” she said.

Spruce root weaving is even more difficult starting with finding the right tree roots. Then the roots have to be split and graded uniformly, with the same width and thickness.

Churchill says preparing materials for weaving takes a lot of practice.

“Especially spruce root because you’re putting it in your mouth when you split it and you’re holding it between your teeth,” Churchill said. “I still have a lot of my mother’s warp that she split and they’re paper thin. I still can’t do that paper thin. I never will.”

Learning from her mother who was a nationally recognized weaver was no small thing.

“It really took me like two years before she thought I was ready. In fact, when I start weaving she burned my baskets for like three or four years,” she said, “because she thought they weren’t good enough because she said, ‘if you tell somebody I taught you and you have a lumpy bumpy basket, I don’t want you to tell them I taught you,’ (laughs) so she burned them.”

Now, at age 86, Churchill doesn’t hold it against her mother.

“I think I’m a lot like her and so she always was very independent and did things her own way,” Churchill said.

Although Churchill is Haida she’s mastered other styles of weaving beyond her own tribe. She said it’s not the pattern or the material that makes it one tribe or another. It’s the technique.

“Haida’s hold it upside down and then the Tsimshian hold it right side up and the Tlingit’s hold it right side up,” she said.

Tlingit’s also use maiden hair fern and grass to decorate. But the knowledge of how to create it, that’s the part that Churchill worries is on its way out. There are efforts to keep it alive though and Churchill is a part of that. But it takes a special motivation…

“You know you get so little for your weaving it actually has to be somebody really dedicated to weaving,” she said. “You could make more being a secretary. You could make more even being a maid.”

Even though weaving can take years to master Churchill feels hopeful. She says there are some excellent weavers around, like in Hoonah, and if they teach others the skills that they know, then the intricate craft will not die out.