Over 30 Petersburg residents are gathered at the local library to learn about bats and a volunteer citizen’s science program. It’s coordinated seasonally through the Alaska Department of Fish and Game but relies heavily on local volunteers like Sunny Rice. She participated last year which meant hooking up acoustic bat equipment to her car and driving slowly down a logging road on Mitkof Island for about an hour.

“When a bat comes its really clear what it is,” Rice said. “So then you’ve heard it and you keep driving around and you’re sort of guessing, if you’re familiar with where you are, ‘Oh, I totally think there’s going to be bats here or maybe there’s going to be bats at this place where I go berry picking,’ so it’s like a treasure hunt kind of.”

Her results were uploaded into an online database that includes information from surveys all over the region.

Southeast Alaska has five main bat species which mostly roost in trees during the summer days and hibernate through the winter in cracks in rocks, talus slopes, and stumps. This creates consistent temperatures and humidity throughout the winter. But the mothers use maternity roosts that are a little warmer, usually in old growth snags on the south side of trees.

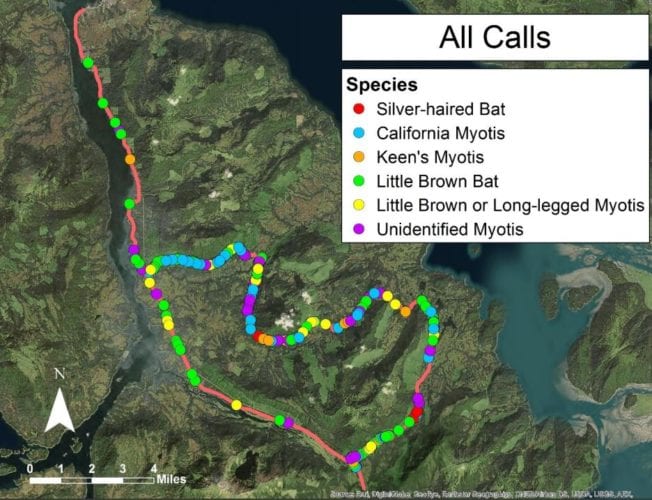

Driving surveys are being done in five communities in Southeast. Over 150 volunteers have recorded over 1,700 bat calls. Most of those were identified by species. The survey has found that most bats are Little Brown Bats except in Sitka, which had more silver-haired bats.

Little brown bats were found all along Petersburg’s route but silver-haired bats were found only on the back Three Lakes Loop portion.

The survey found just one hoary bat in the entire region, which was in Haines last year.

Scientists are in a hurry to learn about Alaska’s populations because of a fungal disease called White Nose Syndrome. Since the disease was discovered a decade ago, it’s wiped out seven and half million bats in the Lower 48. It irritates the bats, causing them to wake early from hibernation and then they starve from lack of food. It can also affect the skin of their wings.

Bats can’t take that kind of pressure because they don’t multiply very quickly. The most common species in Southeast—the Little Brown Bat—lives for over thirty years and the females have only one pup per year.

Volunteer bat surveys are starting to paint a picture of what bats are like in the Southeast. Courtesy of ADF&G

“And so we’re racing against the clock,” says Tory Rhoads, a scientist with the state, “to try and establish any information we can about bat populations in the event that White Nose Syndrome comes to Alaska.”

Besides collecting regional data, Fish and Game has partnered with British Columbia on educating the public about bat trans-locations. That’s when bats accidentally hitch a ride in things like rolled up camping gear or in Christmas trees from farms and end up hundreds of miles away. Rhoads says the bats most common mode of hitchhiking is by boat.

“Given that Southeast Alaska is a very maritime dependent industry not just with our cargo but also with our fishing vessels a lot of which are docked down in Washington over winter and then come here in the Spring that is where we are most vulnerable,” Rhoads said. “And it isn’t too far of a stretch to say that if White Nose comes to Alaska it could very, very likely be by way of a stowaway bat on a ship somewhere.”

So why care about bats?

Well, for one thing, all of Southeast’s bats are major insect eaters. Just one bat can eat 5,000 insects a night. They navigate in the dark using sound or echolocation. They make clicking noises and those sound waves bounce off objects letting them know where things are.

Steve Lewis with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game has been studying bats for over 20 years.

He takes out a little metal box that fits in your hand. This bat detector can translate bat calls into something human ears can hear. He asks a boy in the front row to lightly rub his fingers in front of the speaker.

“I’m going to divide the sound of your fingers by eight,” Lewis tells the boy.

The box is used during the driving surveys, attached to the top of a volunteer’s car. It records bat calls while a GPS tracks the location. Volunteers cover the same route, at the same 20 mile per hour speed at the same time of day, 45 minutes after sunset.

Lewis, Rhoads and their colleagues use the winter months to sift through all of the collected data. The information is uploaded online for the public to view.

The bat survey equipment can be checked out through the Petersburg library. It’s reserved for a week at a time April through August. The volunteer coordinator is Chris Weiss. Volunteers in Juneau, Haines, Sitka, and Wrangell are also participating in the program.