7th grade computer science students work on their Minecraft project. In the front row from (left-right): Sean Spigelmyre, Latham Johnson, and Evelyn Anderson. Photo/Angela Denning

To the adult eye it might look like these 7th graders are just playing a computer game. They’re at their desks hunched over laptops, eyes darting around a virtual world. But this Minecraft is different than what kids play at home. The access is secure. Only the students and teacher can get in. And, there are assignments.

“Everybody here is working on the same world just in different places,” says Latham Johnson. “We have different projects we have to do. Like right now, we’re going to start working on a mine and we’re going to have a mine cart leading to that mine so we can transport stuff back to our house.”

That’s a house that they build…and a mine that they build.

Minecraft is part of a semester long, exploratory course, which lets the school design the program.

Jon Kludt-Painter is the Technology Director. He teaches Mac Tech in the high school and this class. Here, students learn a little programming and engineering.

“First project is just basic skills and they’re showing how to use red stone,” Kludt-Painter says. “And creating invertors, and clocks, and so pistons, the mechanics of those things.”

I ask him what red stone means and he says we should ask a student.

“Redstone is a property similar to electricity as humans use it,” answers Kara Newman.

Her team is in the back of the room. She says they are working to re-establish their settlement to get more privacy from other students.

7th grade students Kara Newman, Leah Kittams, and Sarrisa Miller work on a Minecraft project together. Photo/Angela Denning

“We used to live on the mainland and we’ve moved to an island on the ocean that’s full of more resources because where everyone is living is very drained out,” Newman says.

Resources like stone or iron.

“We were running out of iron,” Newman says. “So, naturally we’re going to have to go elsewhere to find what we need.”

Teammate Leah Kittams has been spending her time getting resources for the group.

“Mostly I go into caves,” Kittams said. “Some of them, they go down into ravines and that’s where you’ll find the most resources.”

Across the room, Sean Spigelmyre types on his laptop. His team is working on something different. They have spent a ton of resources on a quarry.

“Instead of us spending the time mining for the resources, it does it for us,” he says.

I ask him how he figured that out. Did he make something to mine for him or was it something he found in the program?

“You have to make it,” he says. “It’s really expensive to make it, it costs a lot of diamonds and iron and a lot of resources. But when you make it it’s really worth it because it mines for you and that’s something that takes a lot of your time in Minecraft.”

The curriculum for the course and instructional videos were created by Petersburg high school students. Junior Van Abbott helped put the syllabus together.

“It really helps with creativity and problem solving,” Abbott says, “because if something’s not working there’s nothing to tell them why it’s not working. They have to go and figure that out themselves, find the problem and then modify it so it does work.”

Abbott also helps maintain the server for the class.

I ask him, “As a junior in high school these days, how often do you use a computer?”

“We use it for everything, basically” he says. “Even math class which is just paper and pencil we use it because our text books are online.

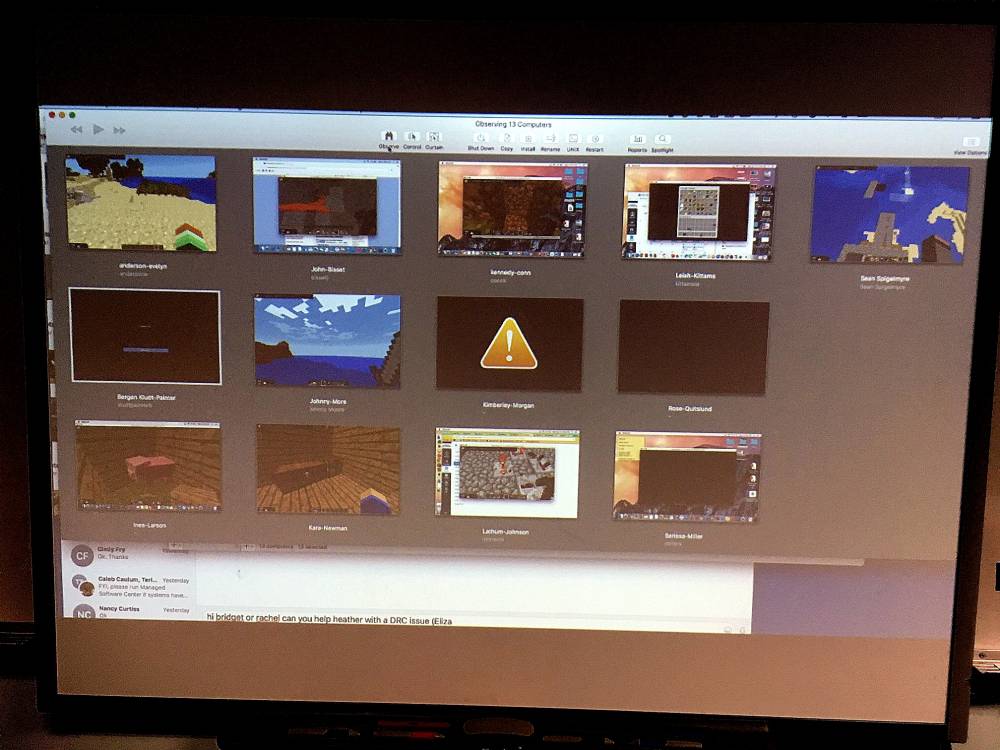

A projector at the front of the classroom shows the students’ laptop computer screens and what they’re working on. Photo/Angela Denning

Back in the 7th grade classroom, Kludt-Painter sits at the front of the room watching the students work. He’s monitoring all the computer screens, which are displayed on an overhead projector.

He says there’s a lack of computer science programs throughout the country and skilled graduates.

“And so there’s a real strong need,” Kludt-Painter said. “Everything now has programming running it. It’s another literacy to understand…what’s going on in the background.”

This computer science course is the last class of the day. But that can be a little tricky. The teacher says they’ve found some students so engaged that they have to ask them to leave, which is a good problem to have.

# # #

Disclosure: Van Abbott is the son of KFSK’s general manager, Tom Abbott.