U.S. Forest Service Archaeologists, Jane Smith and Gina Esposito, record petroglyphs on the side of a rocky wall. (Photo courtesy of the U.S. Forest Service)

Along Petersburg’s main downtown street, Ross Nannauck III is selling his artwork from a table on the sidewalk. His hair’s pulled back in a ponytail under a leather hat that’s painted with Tlingit design in red, black, and turquoise.

Nannuack enjoys talking about his carvings and paintings. He’s sort of a culture bearer, teaching about Tlingit artwork and history to Petersburg tourists and students.

Although Nannauck knows his Tlingit name he was never taught the language. His grandparents’ generation didn’t pass it on.

Ross Nannauck III sets up his artwork to sell in downtown Petersburg. (Photo by Angela Denning/KFSK)

“Assimilation has taken a big toll on our culture,” Nanuak III said. “For a hundred years we were told to forget our ways. We were told our totem poles and our carvings were works of the devil and we should burn them. There’s a disconnect of just who we are.”

Still, artifacts are everywhere on Mitkof Island showing a long history of indigenous people.

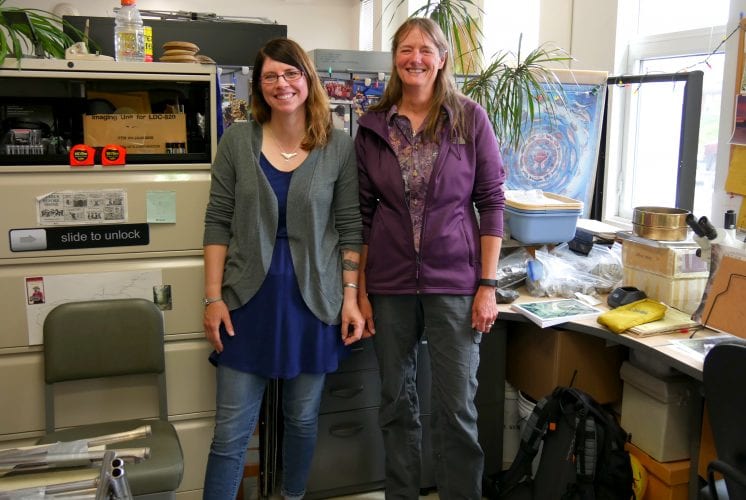

Jane Smith and Gina Esposito are archeologists for the U.S. Forest Service in Petersburg and it’s their job to keep track of artifacts found in the area. Their offices are on the second floor of a downtown building. And it’s just what you’d think it’d look like: maps on the walls, shelves of rocks and bags of soil samples, a yellow hardhat on a back pack on the floor.

“As you can see we could use more space,” Esposito said.

“It’s organized chaos,” Smith chimed in.

Esposito points out some tools in the office.

“We have soil probes that help us find shell midden sites,” Esposito said.

Shell midden sights are like prehistoric trash piles. Esposito says that Tlingit ancestors left mounds of shellfish remains, charcoal, and fish bones.

U.S. Forest Service Archaeologist, Gina Esposito, records a shell midden site, which indicates where people used to live. (Photo courtesy of U.S. Forest Service)

“After they would harvest and eat and process they would just toss it outside their homes or outside their campsites or at their villages,” Esposito said. “And over time that builds up.”

The rain forest grows over the piles so the soil probes are used to find them. These sites indicate where people were living for long periods of time. And that’s what Esposito and her colleague recently discovered less than a mile from Petersburg.

“Right across from town we’ve found evidence that there’s village sized sites across the Narrows,” Esposito said.

The site was dated to 1,120 years ago.

On Mitkof Island itself, they’ve discovered a 5,000 year old fish trap. In fact, large scale fish traps of various ages have been documented in all the major waterways on the island.

Smith and Esposito have worked together as an archeology team for 20 years. Smith says their oldest discovery near Petersburg is a 10,000-year-old site containing stone tool remnants. It was also on found on Kupreanof Island near Petersburg.

U.S. Forest Service Archaeologists, Gina Esposito (left) and Jane Smith stand in their office. They have worked together for 20 years helping to track over 900 archeology sites near Petersburg. (Photo by Angela Denning/KFSK)

The pair tracks over 900 archeology sites including several rock paintings and carvings. Smith says they keep fastidious notes of the materials they collect and the GPS coordinates of the sites.

“One of the reasons we want to know where they are is so when the Forest Service does an action, like builds a road or puts in an outhouse or whatever they’re going to be doing that might be a ground disturbing activity, we know where the archeology sites are so we can avoid them,” Smith said.

Smith and Esposito work with Petersburg Indian Association, the local tribe, to try to connect what they’ve found in the field to traditional knowledge. The locations of the sites are not shared with the general public for fear of vandalism.

But the story that’s been perpetuated publically is a different one. Published articles (here and here, for example) say that Mitkof Island was never inhabited permanently by Native people. It was an occasional stop over for fishermen and hunters for the past few thousand years. But that’s not the entire story.

This pictograph of canoes and sun is located near Petersburg. The exact location is kept secret for fear of public vandalism. (Photo courtesy of U.S. Forest Service)

“You know, it’s kind of emotional really,” said Brenda Norheim, a board member for the local tribe.

Like other Petersburg residents, she’s grown up being told that no one was living around Petersburg when white settlers arrived. But that left a hole to her past. Where were her people? She didn’t learn the answers at home. When her mother was growing up in Petersburg there were signs that read, “No Natives”. She wasn’t told traditional stories or taught the Tlingit language by her elders.

“Natives weren’t allowed to buy land, so you know, were they just not here because somebody said they weren’t here?” Norheim asked.

Ross Nannauck III carves a wooden ladle while selling his artwork in downtown Petersburg. He was not taught the Tlingit language by his elders because his grandfather’s generation was shamed for their cultural beliefs. (Photo by Angela Denning/KFSK)

Some of these questions might never get answered. What Norheim hopes for now is that the archeology finds bring a shared history to town, one of indigenous Natives and Norwegian settlers.

Back on Petersburg’s main street, Nannauck watches the cars go by and says he’s not surprised by what the archeologists have been finding.

“When we talk about ourselves we say that we’ve been here since time immemorial,” Nannauk III said.

He says the science just adds to what he already knows, that his people have been living on and around Mitkof Island for a very, very long time.