ADF&G biologist, Tory Rhoads (right) talks with Doug and Margaret Fleming at a bat monitoring presentation in Petersburg, Feb. 28. (Photo by Angela Denning/KFSK)

Scientists with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game are once again looking for volunteers to help survey bats around Southeast Alaska this year. KFSK’s Angela Denning reports from Petersburg:

Petersburg residents are gathered at the public library to learn about bats in Southeast and how they can help monitor them. The citizen-based bat program has been around for four years in Southeast. Last year over a hundred volunteers participated. Through that, six different bat species have been identified. But scientists don’t know a lot about them like where the bats roost in the wintertime.

“I think for this year that’s our major focus,” said Tory Rhoads, a scientist with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. “It’s been an unanswered question and a study that we haven’t really been able to go back and do to take a fresh crack at it.”

They are making some headway. They’ve learned that most bats are found in Juneau, followed by Wrangell and Petersburg. The further north you go in the region, the less diversity of the species. Myotis bats are the most common except for in Sitka and Juneau, which have about an equal amount of silver-haired bats.

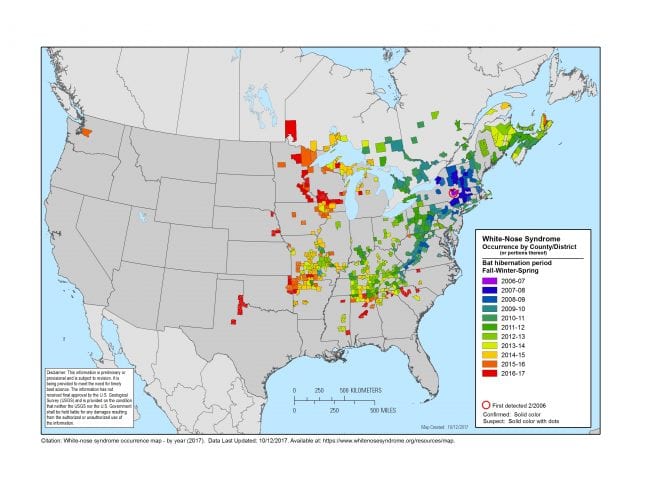

And scientists do know that Southeast bats could be threatened by a spreading disease that’s killed millions of bats in the Lower 48. White-Nose Syndrome is a deadly fungus that causes white fuzzy growth on bats’ skin and damages their wings. It grows in cold climates and affects bats while they’re hibernating. It’s spread across the country over the past decade and has been found in Washington state.

“If White-Nose were to come to Alaska we aren’t going to know,” Rhoads said. “We don’t have the usual tools that they have in their tool bag in other locations for monitoring for the spread of White-Nose, which is how it’s detected in other areas.”

This map shows the spread of White Nose Syndrome as of December 2017. The deadly fungus has killed millions of bats in the Lower 48. (Image from https://www.whitenosesyndrome.org/)

Less bats could really affect the insect population. The little brown bat—the most common in Alaska—can weigh the same as a nickel or a sheet of office paper. But just one can consume up to 5,000 insects a night.

The U.S. Geological Survey warns that bat declines are expected to have substantial impacts on the environment and agriculture because the bats eat insects that damage crops and spread disease.

But bats are tricky to monitor because they’re nocturnal. And you can’t tell some of them apart just by looking at them. So scientists rely on acoustic monitoring, recording the sound they make through echolocation.

To record a bat call volunteers drive a specific route 45 minutes after sunset. There’s a microphone attached to the roof of the car by a magnet. A cable connects it to a bat detector in the car. There are two people, one to drive 20 miles per hour and the other to watch the equipment. In Petersburg, the route makes a loop on Mitkof Island and takes about an hour and half to complete.

The state also runs 15 stationary bat monitors throughout the region. They can record bat activity all night, every night in specific locations. In Petersburg they’ve had a monitor at Blind Slough the last three years.

“So, using the driving survey data combined with the stationary monitor data, if we see a really drastic drop in calls that’s going to be a really big red flag for us,” Rhoads said.

This Myotis bat carcass shows how tiny the flying mammals are. The little brown bat weighs just 5-14 grams. (Photo by Angela Denning/KFSK)

The state also has a tagging project in Juneau that has helped them locate eight roosting sites. They’ve learned that the bats like deep forested scree slopes. And even though the bats aren’t hibernating together in caves like on the East Coast they are gathering in the same areas to roost.

“We know where they overwinter on those two ridge lines outside of Juneau,” Rhoads said. “The thought was we could kind of extrapolate from there and see if we can identify more of these locations in other communities.”

Bats are a particularly vulnerable species because they don’t reproduce quickly. They raise just one pup a year so a disease could quickly decimate a population.

The tiny flying mammals are also long-lived. Little Browns can survive over 30 years in the wild.

So scientists hope establishing population trends will help them track White-Nose Syndrome if and when it does arrive in Alaska.

Results from the citizens science bat monitoring program can be found at the ADF&G website. There you can see what bat calls were recorded in what communities and on what days. You can also find local contacts for the program throughout the region.