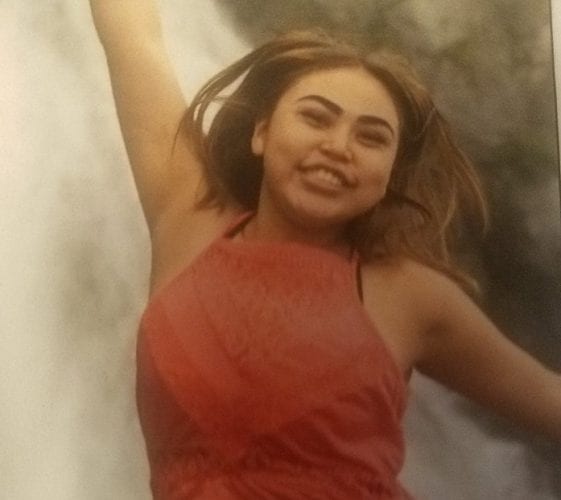

Jade Williams was 19 when she died last year. She is remembered by her father, grandmother, and other friends and family. (Photo courtesy of Grace Gordon Duncan)

Like many communities in Alaska, the Village of Kake has an on-again, off-again history of local law enforcement. A year after the tragic death of a teenage girl – a case that still hasn’t been solved – the lights in the Village Public Safety Office are now back on. At least, they will be again in November, when the VPSOs return from training.

Driving around Kake is something Joel Jackson spends most weekend evenings doing. He is the Kake Tribal Council President and sort of an unofficial guardian for this town of 600. When he was younger, Jackson was the Village Police Officer, but over the decades the town has often gone without any.

“They come and go,” he said, “and when we didn’t have any police officers I answered calls. Because nobody else was doing it.”

He volunteers with Emergency Medical Services, so he’s one of the first people to know when someone needs help in Kake. Like last August…

“I got a text message saying there was a young lady that was unresponsive,” he said.

The young lady was Jackson’s cousin’s daughter, Jade Williams, who had turned nineteen just three days earlier. Her father was away working on a fishing boat and her grandmother was also out of town. There was a party at their house. By 9:30 that evening the neighbors were calling Alaska State Troopers because Williams wasn’t breathing.

“By the time I got there they had already started CPR on her,” Jackson said, “and then they brought her up to the health center…”

…where Williams was pronounced dead. A year later, the case still has not been solved. State Troopers will not comment on an open investigation, but the incident report classified Williams’ death as suspicious. Jackson said there was alcohol involved and neighbors later told him it had sounded like people at the party were fighting.

“From when I talked to the troopers here, it was a homicide. Somebody killed her. Blunt force trauma,” he said.

A Wildlife Trooper responded by boat from Petersburg, 65 miles away. Blue-shirt troopers – the state police trained to investigate people crimes – arrived the next afternoon from Juneau, traveling more than 100 miles.

“It was a little bit faster than the last one,” he said. “Probably about 12 hours. Something like that. And same thing, we posted people around the house so no one could get in.”

When he referenced “the last one,” he was talking about Mackenzie Howard, a 13 year old who was murdered in Kake five years ago. Her family has planned a memorial for her in August. Howard’s and Williams’ cases exist alongside thousands of Native American and Alaska Native women who have been murdered or gone missing. It is widely known that many of these cases go uncounted. Howard’s case was solved, and a local teenager was charged for her murder.

“’Pretty tough time for us. Still is. We kinda walk around on pins and needles because we know both families,” Jackson said. “We’re trying not to say anything that would get one or the other upset.”

Small town relationships are one challenge to having law enforcement across Alaska. It can be an intense, lonely job. Jackson was police officer during an especially difficult time, and quit after only about two years. He explained, “the last year and a half I was chief of police we had 15 suicides. We were known as the suicide capital of the United States. After the last one I just decided I had enough.”

Jackson was the first on the scene every time something terrible happened in a town where he knew everyone. The suicide crisis in Kake ended, thanks in part to a group of community leaders who started brainstorming solutions.

“Culture camp for the kids was one of the first ones. We just had our 30th anniversary of the culture camp. So that’s kind of a testament to trying to get our young people back into the culture – back into our way of life,” Jackson said.

All this to say, Kake has pulled through hard times before, and the interconnectedness of the community has not just exacerbated grief; it has also aided in resilience.

Organized Village of Kake Council President Joel Jackson sits outside the totem pole that went up when he was in high school. Jackson went on to work in the oil fields and returned to Kake, serving as Village Police Officer in the late 1980s. (Photo/Alanna Elder)

The day after Jackson and I talked was the day of Kake’s 24th Annual Dog Salmon Festival. Multiple people remarked there that was nice to see friends and family all in one place, having fun, and not at a funeral. One of the town’s new Village Public Safety Officers, Dean Cavanaugh was there, sitting in civilian clothes above the dunk tank. There was a line of mostly teenagers who paid five bucks to try and knock him in.

Cavanaugh grew up in Kake, spent the last few years in Anchorage, and moved back in 2017.

“I got a family now,” he said: “two boys and a fiancée.”

He needed a job, and a couple of local leaders suggested he take the open VPSO position. It meant something that they thought he could do it, plus, “this was one of the more secure steady jobs, full-time. You get to get all of your hours every week,” Cavanaugh said.

VPSOs are paid through state grant funds, generally hired by native non-profit organizations, and trained by State Troopers. After training they can be armed with tasers, spray, and batons, but not guns. Central Council Tlingit and Haida recently hired two VPSOs for Kake.

Cavanaugh’s partner Ruel Hines said their duties actually go beyond law enforcement. “We’re the public servant for the area, so wherever we could help we lend a hand,” he said.

Officially, they work as EMTs, search and rescue, firefighters, and police. Until mid-November, Cavanaugh and Hines will be away from Kake attending a four-month training. As non-profits grapple with how to fill vacant VPSO positions across Alaska, Kake residents will be waiting for theirs to return. Also waiting is Jade Williams’ family. Her father and grandmother have left town to heal and wait for answers on the death.