Leconte Glacier is located Southeast of Petersburg. (Photo by Angela Denning/KFSK)

Leconte Glacier rises 200 feet above the waterline in a bay southeast of Petersburg. There’s another 500 feet of it under the water, with giant blocks of ice regularly breaking off. To safely collect data, a team of scientists last year created remote controlled unmanned kayaks to go near the surface of the ice.

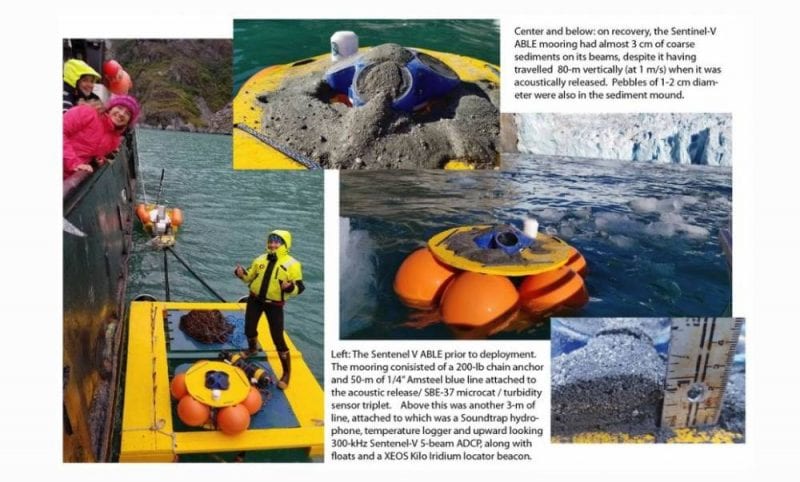

This year, technology advanced even further and scientists have gathered more information about how the glacier is retreating. Specifically, how the ocean water is eroding the surface of the ice. They used a kayak towing a raft. It carries a thousand pounds of equipment, which scientists dropped to the ocean floor in different spots in front of the glacier. They stayed there for two weeks.

“Nobody’s ever tried to do this before,” said Jonathan Nash, an oceanographer who helps lead studies at the glacier. “So this is kind of like sending off a little Mars rover of something. So, we sent it a little code, it went beep, beep, beep, beep booo, and then the instrument said, ‘I’m here’ and it came to the surface.”

That alone was an engineering feat but the new data it recorded was even better.

(Aerial video of an unmanned kayak pulling a raft of equipment in front of Leconte Glacier in September. Courtesy of Jonathan Nash/exploreice.org)

Scientists had already collected measurements along the glacier of currents, temperature, and salinity but nothing constant.

“So there’s cycles in tides, there’s changes in wind, there’s changes in the temperature of the ocean water,” said Nash, “and then there’s changes in things like the rain fall.”

Leconte is like a laboratory for glacier scientists. It’s accessible and it’s the southern-most tidewater glacier in the northern hemisphere. What they learn there can translate into glacial melt research happening in other places like Greenland.

Nash, who is with Oregon State University, and other scientists, have been researching Leconte for two years with funding by the National Science Foundation. That wrapped up in 2017. New funding from the National Geographic Society allowed them to keep going.

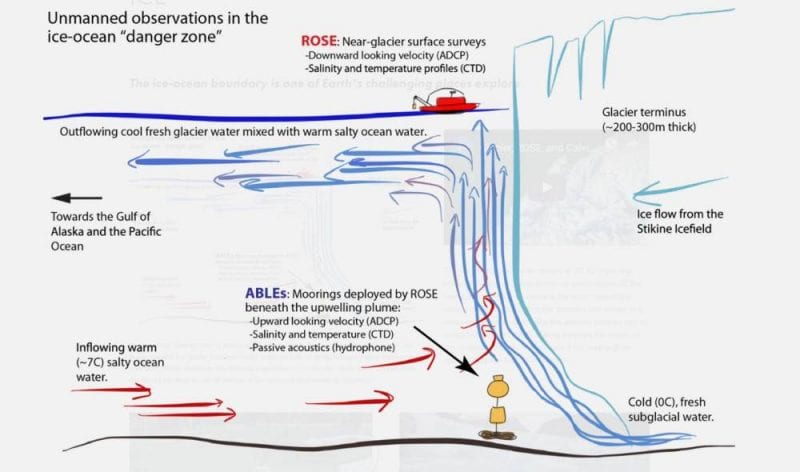

The team has been focusing on a process called feedback. That’s where a fresh water river running underneath the glacier meets heavier salt water. The fresh water rises hundreds of feet to the surface in front of the glacier pulling with it warmer salt water. The more feedback occurs, the faster the glacier erodes.

This image illustrates the process of feedback. (image courtesy of Jonathan Nash/exploreice.org)

Recording in front of the glacier for two weeks is giving researchers a much more detailed look at the variables. They’ve learned that the ocean bottom near the glacier is not stable. In three days it rose 20 feet, then dropped 20 feet, and then dropped another 20 feet.

“And so the terrain down there, we actually don’t know what it looks like but it’s an extremely dynamic spot,” Nash said.

They’re also finding that the rate of ice melt from feedback is greater than they predicted, which would change their previous models. Nash says international climate models include general rates of glacier erosion.

“But there’s no physics in them,” he said. “What we’re hoping to do is get all the components of that physics together so that we can put those into one of these models.”

Besides the new data collected at Leconte, the scientists continued other research such as capturing images of the glacier from various angles above and below the water.

And they recorded the sound of the glacier, which could be another way to study how fast it’s melting.

The remote controlled kayak pulls instruments on a raft near the face of Leconte Glacier in September. The equipment was dropped to the bottom of the ocean for two weeks to collect data. (Photo courtesy of Jonathan Nash/exploreice.org)

“Glacier ice has little pockets of air inside and that air is at super high pressure and when it melts they all go “pppsstt” and pop and make a hissing sound that you can pick up,” Nash said. “And so the more hissing, the more melt.”

They’ll work on the collected data over the next couple of years coming up with a new model they can test on other glaciers, like in Greenland. Nash says current models show ice melting there would raise sea levels a few feet within a hundred years. If all ice there melted it could rise 20 feet eventually.

These instruments were sent to the bottom of the ocean in front of Leconte Glacier to gather two weeks of data in September. (Photos courtesy of Jonathan Nash/exploreice.org)