A fossil of a marine reptile in Southeast Alaska has officially been declared a new species. The 220 million year old Thalattosaur is older than the dinosaurs. And as Angela Denning reports from Petersburg, Tlingit elders have named it after a well-known creature in their traditional stories.

It was nine years ago that U.S. Forest Service Geologist Jim Baichtal helped find the one-of-a-kind fossil. He and a group of others were walking along the beach in the Keku Islands. The area is known for fossils that moved from the tropics in the Pacific Ocean to Southeast Alaska through tectonic activity.

It was a very low tide when they saw what looked like a black rockfish skeleton on a lighter gray background. Baichtal knew it was something special.

“We don’t have dinosaurs, we have Triassic marine reptiles,” Baichtal said. “That’s kind of our fossil here in Southeast Alaska.”

The fossil, about a foot and a half long, showed a reptile with a big tail like an iguana or alligator. But Baichtal needed an expert opinion.

“So, I set out on the outcrop and taught myself how to take a photograph on my old flip phone,” said Baichtal, laughing. “It’s the very first time I’ve ever taken a picture to send to Pat and describe to him what we were seeing.”

Pat is Pat Druckenmiller a Paleontologist and Director of the Museum of the North at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. He looked at the photos and not only knew it was a Thalattosaur but noticed the unique pointy shape of the reptile’s head.

“We knew right away without a doubt that this was a new species,” Druckenmiller said.

But that was only the beginning of a very long process. They waited a month to remove the surrounding rock at the next low tide cycle. It took three years removing the fossil from the rock in the lab. Then it was three more years to compare it to other similar fossils in the world in order to confirm that it was, in fact, a new species.

“We need to compare every single, little, gory detail of every bone to that of other species that are found elsewhere,” said Druckenmiller.

That meant trips to China where most of the Thalattosaur specimens are kept. In total, it took nine years for the fossil to be processed and peer reviewed before it was published as a new species, February 4.

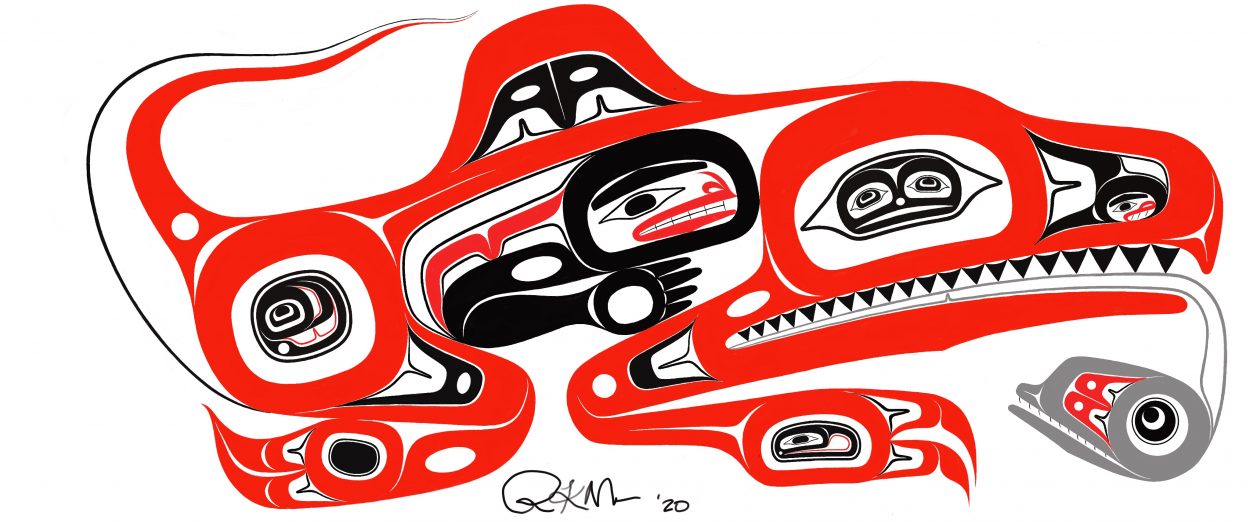

The fossil is not just known as the new Thalattosaur species. It’s been named Gunakadeit.

“Gunakadeit comes from our oral tradition so it’s already an existing name,” said Dr. Rosita Worl, President of the Sealaska Heritage Institute. She’s Tlingit and an anthropologist.

Worl says clans usually own names but Gunakadeit is owned by all Tlingit people as part of their oral tradition. It’s a sea monster legend that helped keep kids safe.

“I just grew up hearing there was Gunakadeit, watch out, you know,” she said. “We were told these stories so that we would be careful and not wonder off by ourselves and always stay within a group otherwise you’re going to get caught by the Kushtaka or Gunakadeit.”

Worl says the scientists asked the tribe if it was okay to use the name. She says they then conferred with their Counsel of Traditional Scholars and checked in with elders in Kake near where the fossil was found. All agreed Gunakadeit was a good name. It’s likely the first time a fossil has been given a Tlingit name.

“I think this is part of the growing awareness and sensitivity about Tlingit culture so we very much appreciated that the scientists came to us,” Worl said.

A second part of the name, joseéae, was added by scientists to honor the mother of Gene Primaky, who first saw the fossil along with Baichtal.

As for Gunakadeit joseéae, Druckenmiller says they can tell a lot about who he or she was just from looking at the bones. They used their pointy snouts to probe into little cracks and crevices in the reefs, searching out soft bodied prey.

“This animal had kind of an enviable lifestyle” Druckenmiller siad. “It lived in shallow marine environments, so coastal environments, on the edge of a tropical volcanic island.”

The fossil belongs to the State of Alaska because it was found in the intertidal zone. It’s currently on display at the Museum of the North in Fairbanks.

In the end, nine years might seem like a long time to declare a fossil is new. But compared to 220 million years…it’s like a blink of an eye.