Petersburg Borough assembly is considering an opinion on a draft senate bill that would give federal land to five Southeast communities–Petersburg, Wrangell, Ketchikan, Haines, and Tenakee Springs. These communities were left out of the 1971 Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, which transferred millions of acres to native corporations all over the state. As KFSK’s Angela Denning reports, the borough assembly discussed the issue at their last regular meeting.

Petersburg Assembly member Chelsea Tremblay wanted to discuss the topic as a follow-up to requests from Native leaders last December asking for the borough’s support.

“I just wanted to bring this to us because we haven’t ever talked about it as an assembly and they’re asking our input as an assembly,” she said.

Tremblay says she felt like there was some urgency to getting a message to D.C. and U.S. Senator Lisa Murkowski who is on the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs.

“This is a pretty important topic to be talking about now and it will be coming at us more in the future,” said Tremblay.

Mayor Mark Jensen agreed saying it would affect not only the native groups but other communities in the area.

“I think this is going to take quite a bit of vetting or looking into to getting all the pros and cons,” he said.

Nearly five decades ago, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act transferred 44 million acres of land to 13 regional Native corporations and about 225 village corporations. The five Southeast communities were left out.

“For no good reason, there was no definitive reason,” said Cecilia Tavoliero, President of the Southeast Alaska Landless Corporation, which has been working to get corporations and land for the five landless communities for decades.

Tavoliero is also a Petersburg tribal member. She says it is a human rights issue.

“When we see other people who are suffering, not being treated equally, it’s not a good feeling especially if you are the one that is the target of that,” Tavoliero said.

A 1993 study by the Institute of Social and Economic Research with the University of Alaska found no significant difference between the five landless communities and others included in ANCSA.

Tavoliero says the newly formed corporations would be able to pursue culture camps educating the young people about traditions like preparing foods and dancing. It would also create jobs and new infrastructure in the communities.

“Professional services, they need utilities, they need construction,” said Todd Antioquia with the group, Alaska Natives Without Lands, which is campaigning for the new legislation.

“If you look at communities even in Southeast here like Goldbelt in Juneau or Hoonah Totem in the village of Hoonah for instance, in the 48 years of their existence they have just contributed in amazing ways through not only job development but community spend,” he said.

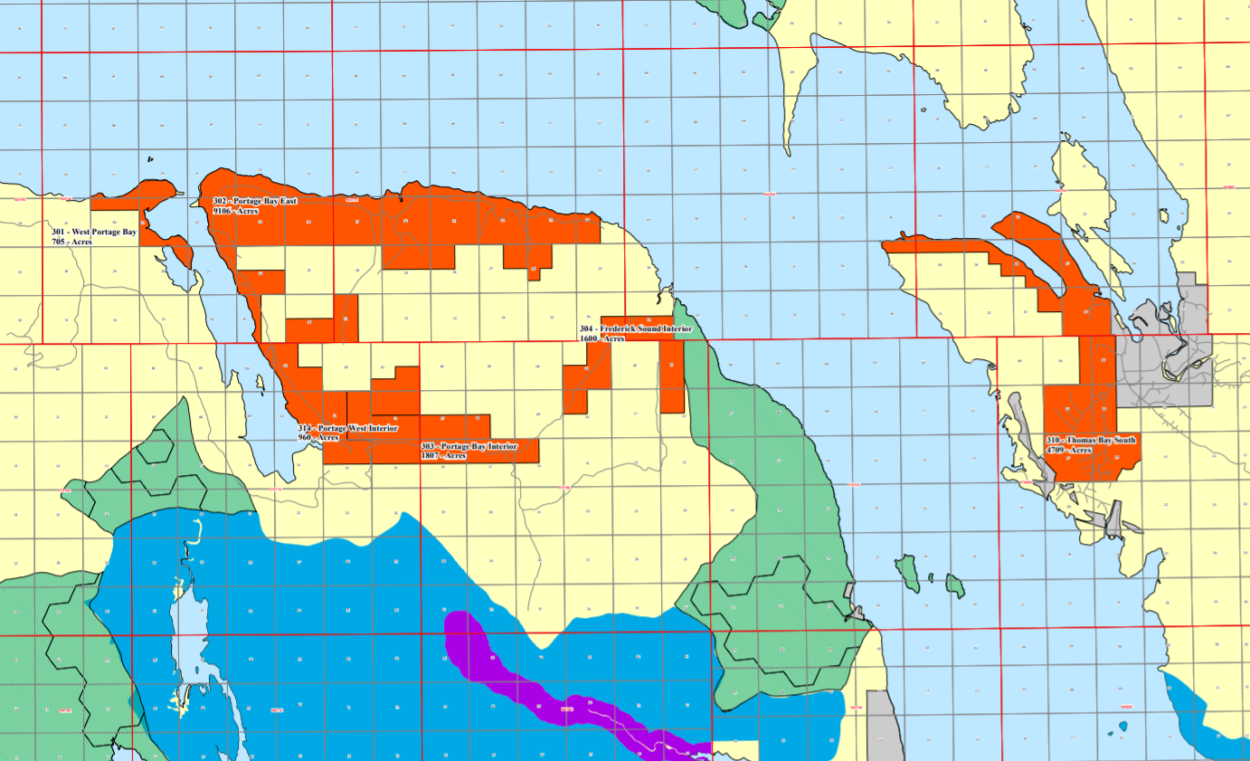

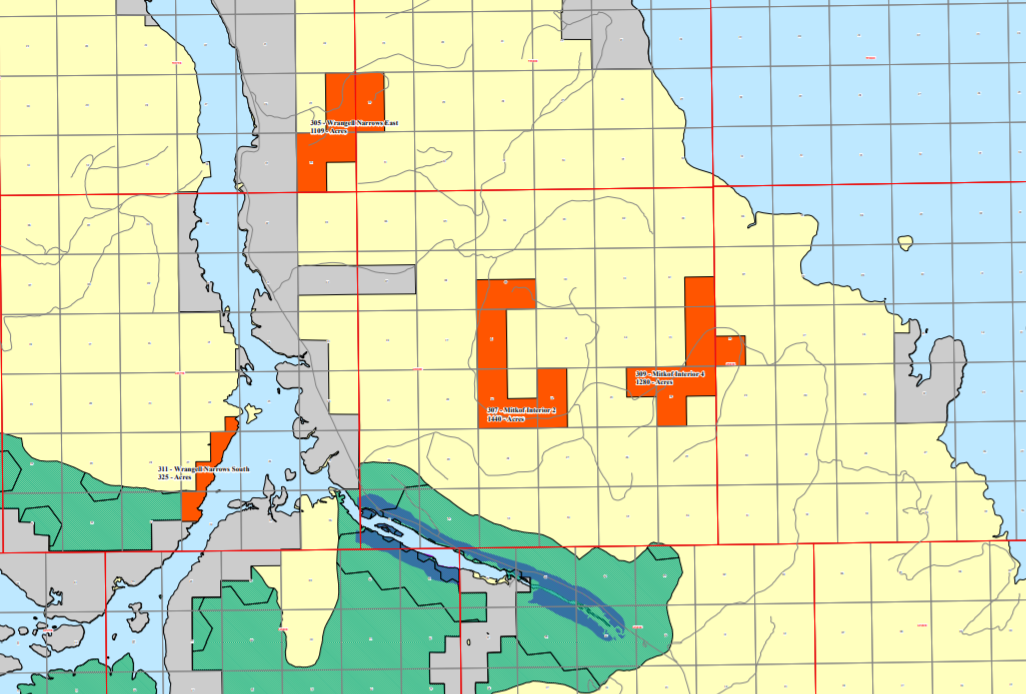

Similar bills have been tried in DC before backed by Alaska’s Congressional Delegation. This latest senate bill includes specific maps with land selected by the communities equaling about 115,000 acres of federal land. The Tongass National Forest has about 17 million acres by comparison.

The selection near Petersburg includes acreage near Portage Bay and Thomas Bay, a few areas in the middle of Mitkof Island, and a small section along the Wrangell Narrows on Kupreanof Island across from Blind Slough.

On Prince of Wales Island, the Ketchikan Landless Community has selected a section of land along Red Bay.

The bill is still in the draft form and Petersburg assembly member, Bob Lynn, says there are still a lot of unknowns.

“There is a tremendous amount of questions yet to be answered that I don’t see answers for here,” Lynn said.

He attended the recent Alaska Municipal League meeting over the phone and said U.S. Senator Lisa Murkowski referenced the legislation there saying there were still legal questions that need to be answered.

Taylor Norheim is the only Petersburg tribal member on the assembly. He told the others that the land selection is not to keep people from accessing areas.

“Just so it’s out there, the tribe has no interest in cutting people off to access to the land,” he said. “If the tribe gets this land they’re not going to say, ‘No white people allowed,’ that’s not what they’re doing.”

Tavoliero agreed.

“All of the other communities with village and urban corporations, they allow public access to the lands,” she said. “Nobody wants to deprive anybody of anything.”

Assembly member Lynn asked if the borough administration could find out more details about the timeline of the draft bill.

Mayor Jensen said that assembly should plan to have public comment before the group drafts any opinion letter.