The first annual Séet Ká Festival focused on bringing cultural awareness and revitalization to Petersburg through workshops and discussions. Part of that process is reclaiming the Lingít language and Indigenous place names. KFSK’s Angela Denning reports:

In Petersburg there are often Norwegian and English words on signage, like at the airport and downtown storefronts. The current town site was established around 1900 by Norwegian immigrants looking for a good spot to process fish. But the Lingít culture goes back thousands of years before that.

Petersburg’s Indigenous name is Séet Ká Kwáan. It means people of the fast moving waters, referring to the Wrangell Narrows in front of town.

At the festival, X’unei Lance Twitchell leads a group in pronouncing Séet Ká. He is an Associate Professor of Alaska Native Languages at the University of Alaska Southeast. He says using a language helps normalize it in a community.

“Do you see it when you walk around? Do you hear it when you walk around?” Twitchell asked the group.

He says adding Indigenous language to signs in public spaces can help, like the words “open” or “welcome”.

“We can see it, and then once we see it, we’ve learned how to make the sounds, we’re going to be curious how to read those things,” said Twitchell.

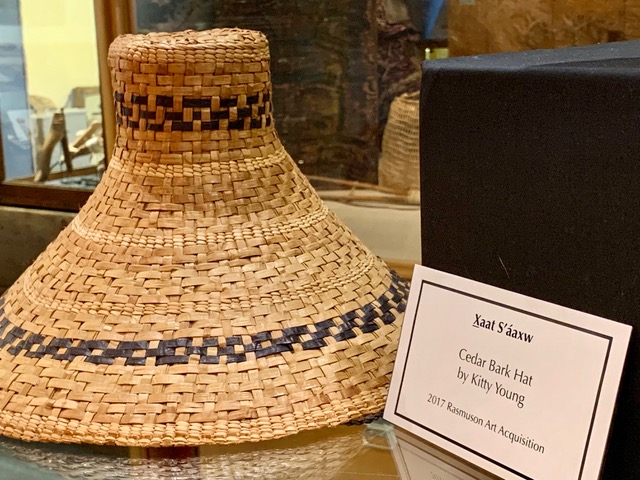

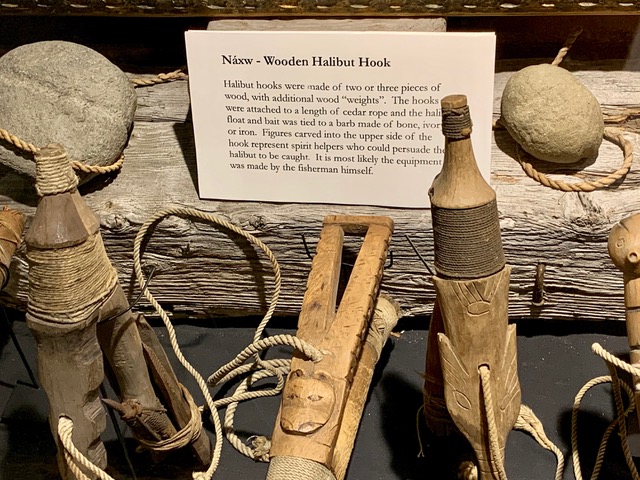

The Clausen Museum in Petersburg is starting to include Lingít signage in its building and that’s something that Twitchell encourages. He says the Indigenous words can be in addition to other languages already present like English and Norwegian.

“Pushing back on these ideas that there’s only room for so many things. Because it was called Séet Ká long before it was called Petersburg,” Twitchell said. “And it doesn’t mean that it also can’t be Little Norway. It can also be “on the channel”, right? And so these things they don’t have to compete against each other.”

Twitchell has been advocating for restoring place names in Southeast Alaska for years.

Thomas Bay is a popular place for boat outings from Petersburg. It’s Tlingit name comes from the shape of the land and water there.

“Taalkuuáxk’u Shaa,” said Twitchell. “So, it’s an open-mouth basket cove.”

A Lingít word for the Wrangell Narrows is Gánti Yaakw Séedi which means burning boat channel or steam boat channel.

Sometimes names on maps can be racist and offensive, like Seduction Point on the Chilkat Peninsula. The English name, which was officially removed in 2020, referenced a sexual assault of Indigenous women by British sailors. (The name was changed to Ayiklutu.)

“So, there’s a problem there that the Indigenous community has to live with these narratives,” Twitchell said. “And it also becomes an insult on top of a violence against people. So then we sort of want to make lists of those and say ‘get that off all the maps’.”

There are offensive place names closer to Petersburg that are being changed but it isn’t a quick process. It often requires coordination between state and federal governments.

Twitchell says another step to normalizing a language is teaching people correct pronunciations for existing Lingít names like Yakatat, Kake, Klawock, Angoon, Skagway, and Hoonah.

“I think there’s resistance at first,” Twitchell said. “You know, someone [might say] why do they want to change the name of Hoonah? It’s always been called Hoonah, it’s just people mispronounce it. That’s all we’re doing is fixing the mispronunciation.”

Another way of reclaiming the language is by simply using it. The more you use it, the easier it becomes. Twitchell says some people might not understand the motivation and that’s okay. It’s part of the process.

“Sometimes if a community doesn’t have a regular presence of Indigenous activity then people get nervous about it and I think they express [that] saying, ‘I don’t think I’m included in this,’ he said. “But really people are saying, ‘I don’t know what to do here. I’m not used to this being present’.”

The Séet Ká Festival was held February 10-15 in Petersburg and online. Guest instructors taught Lingít, beading, formline, and held discussions on topics such as racial equality.