Petersburg High School has seen an uptick in e-cigarette use, also known as vaping. The school is not alone in this issue; rates of teen vaping in Alaska are on par with the lower 48.

School administrators in Petersburg say that more kids are vaping this year than in years past. Middle and High School Principal Ambler Moss said at a school board meeting there was at least one group of kids vaping in school.

“We did have a situation early in the year where four students were vaping in the bathroom,” said Moss, “but miraculously because we found no instrument, we just knew it had taken place.”

The school hasn’t actually caught many kids vaping. But students have said vaping is going on.

Charlotte Martin is seventeen and the student rep for the School Board. She says vaping isn’t widespread but some kids are vaping during school, probably to seem cool.

“You’re trying to look cool,” said Martin, “with maybe something that someone that’s a little younger would do to try to fit in with some of the older kids… I think most people would say, it’s not very cool. It’s kind of cringey.”

Part of the problem is that it’s easy for parents and teachers to miss the signs of vaping entirely. Compared to cigarettes, vaping may have little smell, or it may smell like flavorings. Kids might know but not always the adults.

“I think a lot of kids know what things smell like,” said superintendent Erica Kludt-Painter. “And then the adults are saying, ‘that smells like strawberries.’”

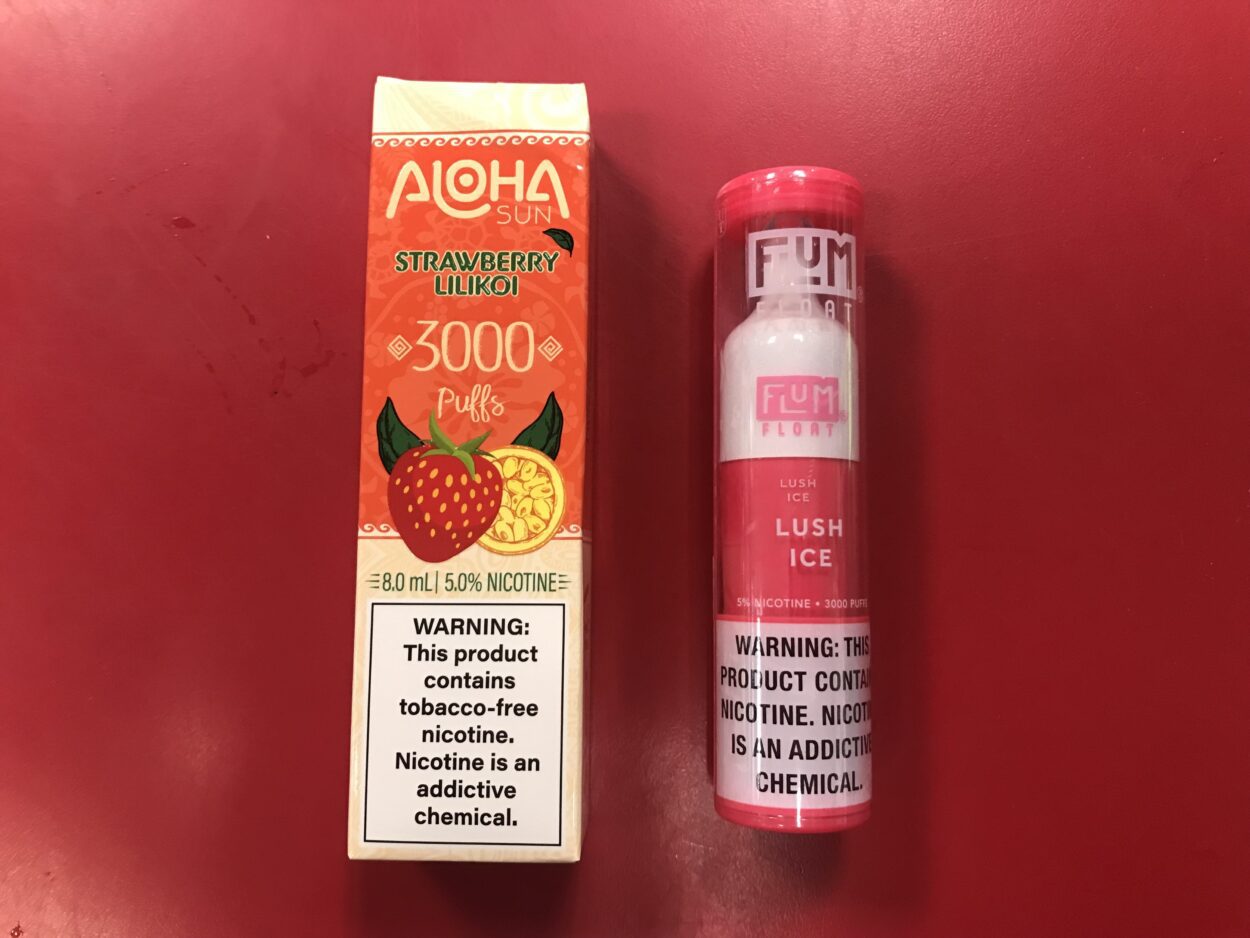

Older vaping devices produced big clouds, but newer ones are more subtle. And people who don’t vape might also have trouble recognizing the devices. They can look like flash drives, pens or highlighters, or even makeup.

Every year the Petersburg high school students fill out the Alaska Youth Risk Behavior Survey, which is anonymous. According to that survey, vaping rates for local teens are on par with the Southeast region and the state. Erin Michael is the Public Health Nurse for Petersburg and Wrangell.

“Petersburg looks at an average about 20.7 percent have in the last thirty days used electronic vaping products when the survey was done,” said Michael “and the state is at 21.6…so very similar numbers there.”

That means about 1 in 5 high schoolers have vaped in the last month and almost 45% have tried it. Nicotine is addictive for anyone. But teens are at greater risk. Charlie Ess is a wellness coordinator for the Rural Alaska Community Action Program—rurAL CAP.

“Because the adolescent brain hasn’t developed a prefrontal cortex for reasoning quite yet,” said Ess, “it’s very susceptible to addiction”

Christy Knight is program manager for the Alaska Tobacco Prevention and Control Program. She says high amounts of nicotine impairs developing brains.

“They still have quite a bit to learn in their lives and nicotine really interrupts that process,” said Knight. “[It] impairs their ability to pay attention, it impairs their impulse control, and it really just is impactful to their ability to learn in a negative way.”

Knight says that because vaping is relatively new, we still don’t know the long term health effects. But we do know some of the ingredients people vape.

“They may contain ultra fine particles,” Knight said, “and those can be inhaled deep into the lungs, of flavorings, such as diacetyl, which is a chemical linked to serious lung disease, volatile organic compounds such as benzene, which is found in car exhaust, and heavy metals such as nickel, tin, and lead.”

Ess says that the word “vape” is actually a misnomer. When people use e-cigarettes, they’re not inhaling water vapor, but aerosolized chemicals.

“Imagine putting a can of hairspray up to your mouth and give it a shot like whipped cream,” Ess said.

According to experts, the most concerning part of young people vaping is that it could mean they are dealing with even bigger issues. Samuel Steinbruegge, a social worker and supervisor at SEARHC’s behavioral health clinic in Petersburg, tells me what he worries about when a kid is vaping.

“The very first thing I think about is what else is going on for that kid?” Steinbruegge said. “Because they’re looking for something to help themselves feel better, in nicotine.”

And he says we need to view habits like these in the context of cultural and intergenerational trauma.

“Structural violence and oppression lends itself to things like alcoholism, then domestic violence, divorce, substance use,” Steinbruegge said.

Teens may also turn to vaping because of stressors around COVID. Steinbruegge says teens go through a developmental phase called individuation, where peer relationships become especially important. COVID lockdowns weakened those peer relationships.

“Not having those peer interactions has lent itself to increased rates of depression, increased rates of anxiety,” Steinbreugge said.

These are problems that Alaska and the rest of the US is also facing. The upside of that is there are regional, statewide, and national programs to help with this very problem.

This is part one of two stories looking at vaping. The next piece will run tomorrow. It will focus on what we can do when teens are vaping—in Petersburg and beyond.