The Petersburg Marine Mammal Center has resurrected its monthly lecture series after a two-year hiatus due to the pandemic. In the last week of February, the center invited Petersburg-based wildlife biologist Toby Bakos to speak about his work with the Forest Service fire militia.

When the number or size of wildfires exceeds a local fire agency’s ability to fight them, they can call in militia support. That support can include help from employees like Bakos — who aren’t full-time firefighters, but who are trained to fight wildfires when needed. Bakos talked about the science of fighting wildfires and what it’s like to be on the front line.

For over 20 years, Toby Bakos has helped fight fires across eight western states. When the order comes in from the fireline, he’s called away from his home in Petersburg for two to three weeks at a time. He said it can be intense work, but safety is their top priority.

“Firefighter safety and public safety always trump anything else — even over houses and structures. And a big component of safety is maintaining your situational awareness. So if something like this is happening, you don’t want to be all of a sudden like: ‘Man, I wonder where that crew is that I’m supposed to be supervising?’ Or, like: ‘Hey, did we tell that group to get out of that road?’ You just need to be really aware pretty much all the time.”

Bakos usually serves as a heavy equipment boss, directing bulldozers on the fire line. Bulldozer lines help prevent wildfires from spreading further out. The lines are built by heavy equipment operators who cut up the ground and remove flammable plant material down to the bare soil.

“So you might have heard of the fire triangle, which is fuel, oxygen and heat,” Bakos explained. “That’s how you can make fire — you have to have those three things. When we talk about wildland firefighting, it includes topography and weather. Fuel is a huge component of that. And so if you have really light fuels covered — but not super intensively, like grass — that’s something to be aware of, because [fire] can move through grass super fast.”

Bakos has also been summoned to help treat areas for wildfires that haven’t happened yet. That’s by starting smaller, more manageable fires in a practice called prescribed burning, or controlled burning. Fire used to be part of the ecology of forests across the western United States. It is an important land management tool — even though, Bakos said, the Forest Service tried to suppress fires for many years.

“When European settlement arrived in the West, they started to suppress fires,” said Bakos. “Fires are seen as bad. In 1935, the Forest Service established the 10 a.m. Policy, which strove to get the fire out by 10 a.m. So what that does to a forest, when you take fire out of the ecosystem: the trees that are more shade tolerant, have a competitive advantage over the ones that aren’t. Some tree species need fire for their seeds to germinate.”

But, Bakos said, the work isn’t all chaos and excitement. He described what downtime was like around the fire camp — including all of its minor, non-lethal challenges.

“Pre-COVID, they used to have a caterer that would set up tables and everything,” said Bakos. “This doesn’t happen anymore, which is actually kind of good. I don’t know if they’ll ever go back to it, because of the amount of what we call ‘camp crud.’ That’s where somebody has a random cold, when you are all touching the same spoons and stuff. It just spreads like wildfire. Now, instead, you go to the caterer. They hand you a box with food and you take off.”

But the element of danger remains. Bakos recalled his closest calls and explained how wildland firefighters identify escape routes from the rapidly approaching flames.

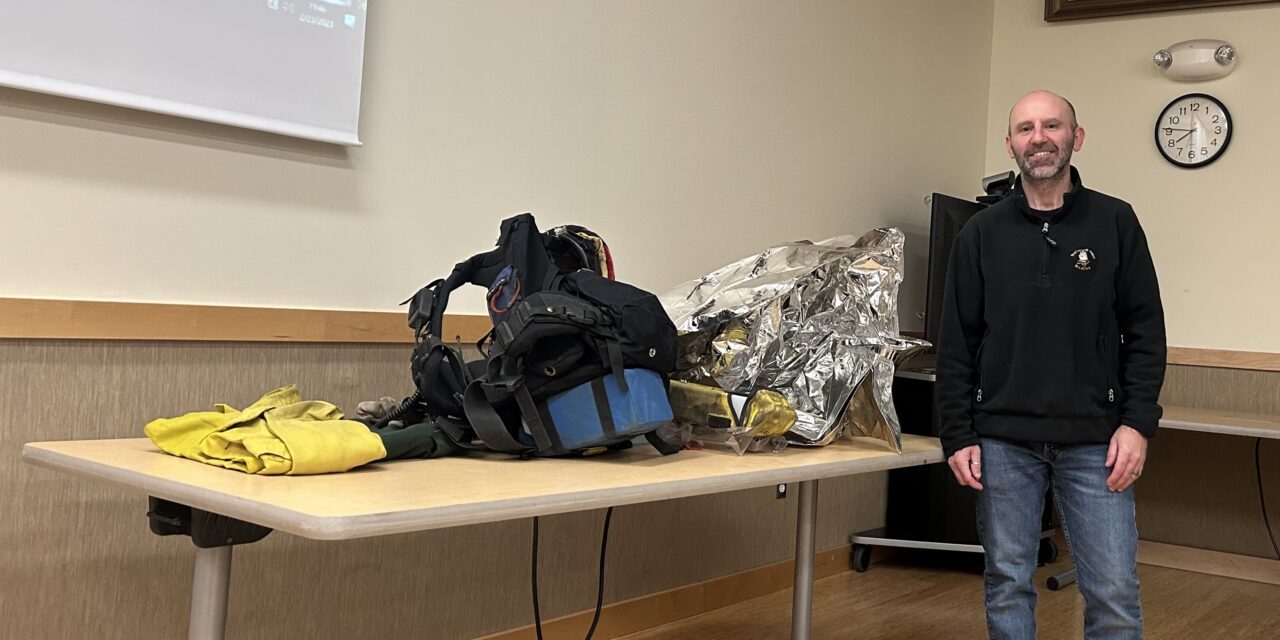

“It’s always good to have multiple escape routes out of someplace,” said Bakos. “Another safety zone is where the fire has really burned wherever you can go to it and just wait. You wait for the fire to burn around you. You don’t have to use a fire shelter, which is that thing on the table over there. You should never have to pull that out.”

Bakos indicates a fire shelter, set out on the table in front of him. It resembles a large sleeping bag made of aluminum foil. Wildland firefighters use fire shelters as a sort of last resort when they become trapped by wildfires. The shelters don’t stand up well to direct flames or longer periods of heat exposure, and cannot guarantee the survival of the user.

This presentation was organized by the Petersburg Marine Mammal Center and the Alaska Sea Grant, and hosted by the Petersburg Public Library.