School counselors and youth mental health support staff in the Petersburg School District say they’re feeling spread thin as they fight for funding to keep their program afloat. They’re worried about elevated anxiety levels among their students that could worsen with proposed state laws.

This report contains details that may be upsetting to some listeners, including references to suicide.

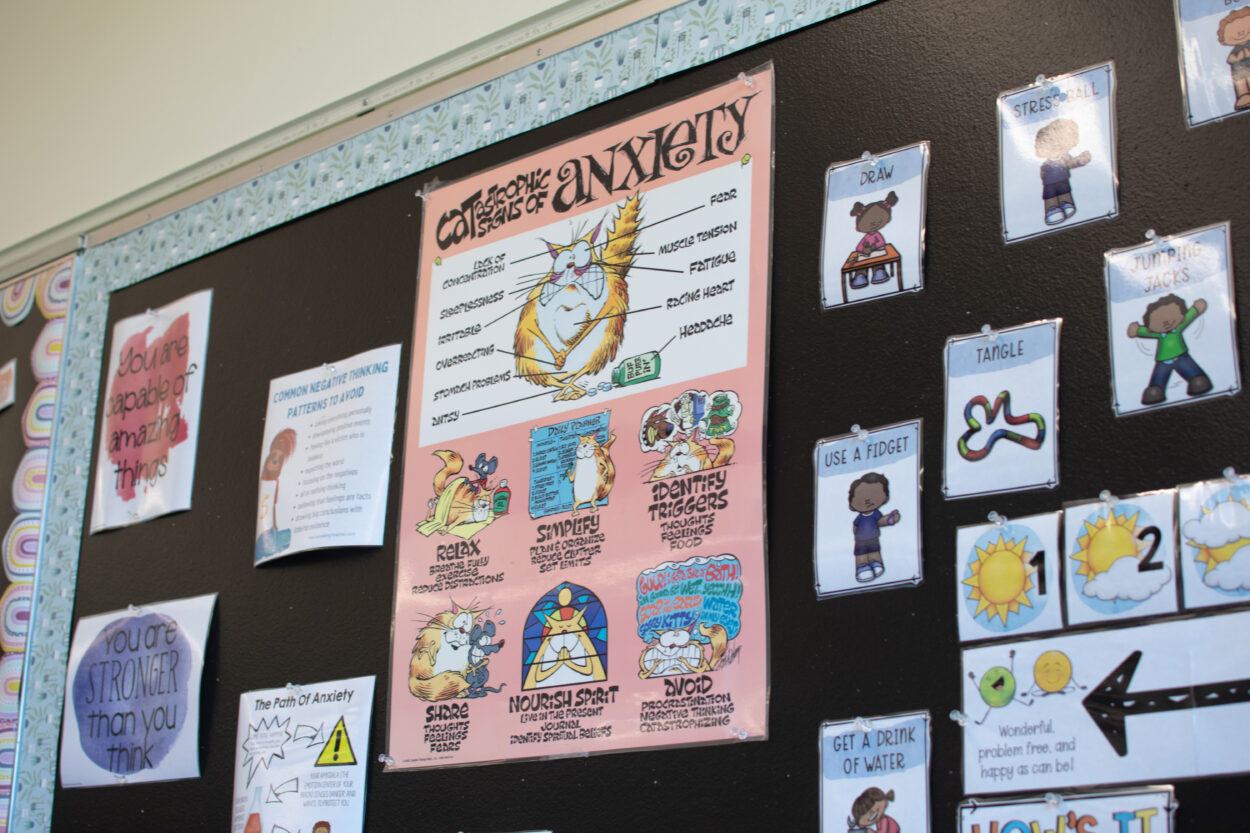

Ashley Kawashima is a mental health provider for Petersburg middle and high schools. She’s also a behavioral health clinician at the local medical center. In the past few years, she said she’s witnessed a trend towards anxiety.

“They’re hearing things at home and they’re worrying,” said Kawashima. “Specifically over basic needs — things are getting more expensive, it’s harder to access certain things. A lot of that anxiety is just coming from those basic needs and figuring out how food is expensive, shelter is expensive.”

According to the Alaska Department of Labor, economic uncertainty from the pandemic is still hanging around. Supply chain disruptions continue to be a problem. And the state’s job growth was among the slowest in the country last year. Kawashima said the kids are paying attention.

“They’re coming to school and they’re worrying like: ‘Oh, I need to think about, like, what I’m going to do for work this summer, because I need to be able to contribute,'” said Kawashima.

In order to support their families, Kawashima said many Petersburg students are looking to join the fishing and canning industries, which are associated with irregular hours and high levels of stress.

On the bright side, the school district’s mental health support staff say many students are comfortable reaching out for help when they need it. Mariah Colton is the student support specialist at Petersburg’s middle and high schools. She said her students are more empowered to seek out mental health support than previous generations.

“I see more students are more likely to reach out — even if it’s just like an email,” said Colton. “Like, ‘I just want you to know I’m worrying about this.'”

Petersburg’s counselors welcome that openness. But they’re worried about legislation that could change how they do their jobs. In March, Gov. Mike Dunleavy announced the Parental Rights in Education Bill, which would require parental consent to change students’ names and pronouns in school. If approved by the legislature, students would also require written permission to join programs related to gender and sexuality.

Colton said, if the bill passes, she expects it will make her job more difficult than it already is.

“If we’re really, really in the business of helping and doing no harm, it’s hard to picture a law that forces us to out students and potentially do harm,” said Colton. “I’m trying not to pre-worry about things — but I am certainly pre-worried.”

That sense of safety is important when they need to intervene in critical situations. Sometimes, Kawashima said, the students will speak up on behalf of each other. Students will refer their friends to her if they’re experiencing a mental health crisis.

“Their friends were like, ‘Hey, I talked to this person, and they were able to help me during this really difficult thing or figure out what to do — and they might be able to help you too,'” said Kawashima. “And it’s nice, because then it’s not just, like, parents [who refer their child to me].”

Kawashima often sees higher needs students — those who have experienced significant traumas, are experiencing suicidal ideation, or exhibiting self harming behaviors. She gets paid through the SAPP grant, or the Suicide Awareness Prevention Postvention program. The $25,000 grant is one of many state initiatives to address Alaska’s high rate of youth suicidal ideation. The Petersburg School District is reaching the end of their current five-year grant period.

Amidst this precarity, Colton said administrative tasks — the things counselors have to do outside of actual counseling — haven’t stopped piling up.

“I see my position being spread more thin,” said Colton. “Where maybe I have to be really protective of my time with students to be able to say no to certain tasks and duties that will fall my way. I have to hold these boundaries, because I know this is important for students.”

Rachel Etcher is the counselor for Petersburg’s Rae C. Stedman Elementary. She said people are an expensive part of education, and that over the course of her career, she’s watched the workforce shrink— and that when their budgets get cut, the staffing shortages that follow sting the most.

“It’s the people who are building this safety net that helps catch kids from falling through the cracks,” said Etcher. “And that’s happening in classrooms, when we have additional teachers aides to help. It’s happening in the lunchroom, when we’ve got people that can do more than just quickly shoveling food out. It’s when they can be having conversations with kids. Those kinds of connections are what saves kids.”

The School District has been a SAPP grantee for many years, and the counselors say the outcome of losing that resource is almost incomprehensible. The Petersburg School District will find out whether or not they will receive SAPP funding for the next five years on Sunday, May 14th.