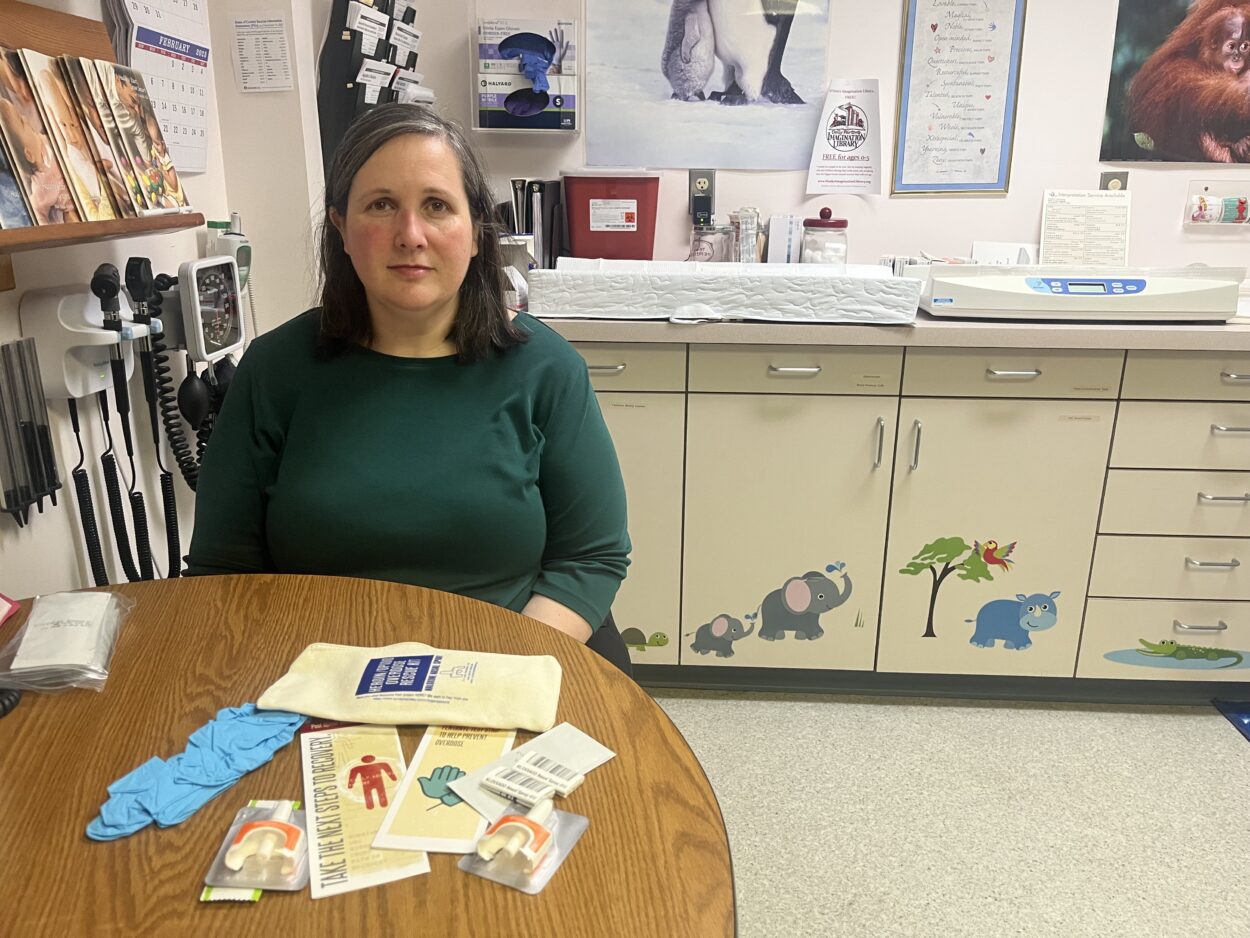

(Photo by Shelby Herbert/KFSK)

Overdose deaths are spiking across the United States — and Alaska is no exception. Last year was the state’s deadliest year on record for opioid overdoses. Naloxone is a life-saving medication that reverses overdoses. And over the last couple years, some groups in Petersburg have redoubled their efforts to distribute it.

But local police leadership has questions about how much it’s actually helping.

Petersburg first responders, law enforcement, and medical professionals know that fentanyl has reached the quiet shores of Mitkof Island. They’re on the front lines of the opioid crisis. They’re seeing larger quantities of fentanyl in town, according to Aaron Hankins, Director of Petersburg’s Volunteer Fire Department and EMS.

“The pills are so small and so potent, and so cheap,” said Hankins. “That means it’s easy to bring a lot into town in a big hurry. Some of the recent busts that they’ve had, they’re bringing 3,000 pills in the bottle that’s not much bigger than a soup can.”

And responders are seeing more overdoses, according to James Kerr, Petersburg’s Police Chief.

“Fentanyl is so potent,” said Kerr. “[We] see people [who] tell us that they tried it for the first time, and the dose was wrong — they end up needing Narcan several times to reverse it.”

And public health nurse Erin Michael said it’s hard to envision a long-term solution.

“It is very, very challenging,” said Michael. “And then being in Alaska makes it even more challenging because they have a significant shortage of mental health counselors — in particular — that handle substance abuse.”

(Photo courtesy of Congressional High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas program.)

But in the short term, some entities in Petersburg are trying to stem the tide of opioid related deaths with Naloxone — that’s a medication that rapidly reverses an overdose. It’s a nose spray administered through a device called Narcan. Petersburg’s public health office is working with several different organizations in town to get as many Narcan kits into as many hands as possible.

Michael said she’s watched local demand for Narcan kits skyrocket over the last couple years. But she said not everybody who asks for a kit is planning on using it on themselves — many want to have one on hand to protect other people. In 2021, she said the office didn’t have massive demand for Narcan, with only 36 different people coming in for kits. Then in 2022, that number jumped up to 234 — and in 2023, they were up to 271.

“So, we are seeing an increase,” said Michael. “I think that the stigma has gone away [about] people having these.”

She said the public health office looks at Narcan like any other item in a first aid kit.

“You would have a mouth shield with your first aid kit, you’d have bandages… [Narcan kits] would be considered another part of your first aid kit in case somebody needs help with an overdose and needs that extra push to help them start breathing again,” said Michael.

It’s easy for anyone to pick up a kit at the public health office. Staff members don’t check IDs, and don’t require that people sign the form for the kits with their real name. They do ask for a phone number, but that’s just so they can call you back in case there’s a recall.

“It’s really helpful for us to be able to call them back and say, ‘Let’s swap out your kits!'” said Michael.

(Photo by Rachel Cassandra/AKPM)

But that easy access is troubling to James Kerr, Petersburg’s police chief. He said it’s frustrating when his officers respond to suspected overdoses, and they see Narcan kits at the scene — just out of reach.

“We see [them] everywhere,” said Kerr. “When we go to search warrants, we’re seeing used Narcan and brand new [kits] ready to be used.”

Kerr said he’s worried that the kits make people who use illicit drugs feel dangerously confident about the doses they’re taking.

“Narcan has [its] place,” said Kerr. “It saves lives, no one’s gonna doubt that — but I also think that it has made people lose [their] fear of the drug. And that’s the sad part. I see Narcan being handed out a lot, but I don’t see as much [being distributed] on the educational side of it.”

The kits Petersburg’s public health office hands out do contain little guides on how to use them, as well as brochures for substance abuse treatment centers in Southeast Alaska.

Aaron Hankins is the director of Petersburg’s Volunteer Fire Department and EMS. He keeps it available at the local Fire Department for anyone who needs it — no questions asked. But he said he’s heard about parties in town where the presence of Narcan kits emboldens illicit drug users to take larger quantities of drugs.

That said, Hankins is totally on board with community members having it on hand to potentially save lives before emergency responders can reach them.

“Remember that these people are people’s sons and daughters; they’re parents,” said Hankins. “Remember that people who suffer overdoses are still human too. [Naloxone] is only one piece of the puzzle that we’re trying to provide to make sure that everyone lives, and they get that chance to go to treatment. “

These kinds of concerns about Naloxone are far from uncommon, according to Dr. Emily Einstein, who directs the Science Policy Branch of the National Institution on Drug Abuse (NIDA). She said she’s encountered skepticism about Naloxone from members of law enforcement — and even lawmakers — from all over the country.

“I think the biggest misconception is where people think that having Naloxone around is going to encourage drug use,” said Einstein. “And the evidence shows that’s just not the case! The reality is that [overdoses] are happening and we need to have the tools available to reverse them.”

Travis Hedwig researches substance misuse prevention at the University of Alaska Anchorage, where he is the Assistant Dean for the Population Health Science Department. He said he’s sympathetic to first responders who doubt the efficacy of Naloxone when they see more kits getting distributed, but overdoses continuing on, seemingly unabated.

“Our law enforcement and first responders have to do a very difficult job,” said Hedwig. “It’s a job that in and of itself is traumatic. It’s a job that, over time, starts to test your empathy — and I don’t mean that as an accusation. Like: ‘Gosh, we’re seeing this uptick. Nobody really knows why — all I know is that I’m having to respond to more people.’ But from my perspective, therein lies the opportunity for more intentional dialogue.”

He said Narcan is an important tool for making a dent in the state’s ever-increasing overdose death toll. But he hopes he’ll see a day when health experts and people working on the front lines of the opioid crisis can stop talking past each other on the issue.

“I personally would want to talk to some of those first responders, because their insight is valuable,” said Hedwig. “I’m not here to deny somebody else’s lived experience, like: ‘Hey, I worked the night shift last night, and I prevented two overdoses!’ That’s real, you know. But I also think we sometimes run the risk of reinforcing our divisions — where there really is potential to be talking with one another, in a more respectful way, in a more holistic way, in a more community-engaged way.”

As for how to solve Alaska’s fatal overdose crisis in the long term? Hedwig said he doesn’t have all the answers. But he said the big-picture solution also has to start with empathy — recognizing illicit drug users as people, making sure their basic needs are met, and reconnecting them with their communities.